The pure stage-one company is not conscious of its domestic orientation. The company operates domestically because it never considers the alternative of going international. The growing stage-one company will, when it reaches growth limits in its primary market, diversify into new markets, products, and technologies instead of focusing on penetrating international markets.

Stage Two—International

The stage-two company extends marketing, manufacturing, and other activity outside the home country. When a company decides to pursue opportunities outside the home country, it has evolved into the stage-two category. In spite of its pursuit of foreign business opportunities, the stage-two company remains ethnocentric, or home country oriented, in its basic orientation. The hallmark of the stage-two company is the belief that the home-country ways of doing business, people, practices, values, and products are superior to those found elsewhere in the world. The focus of the stage-two company is on the home-country market.

Because there are few, if any, people in the stage-two company with international experience, it typically relies on an international division structure where people with international interest and experience can be grouped to focus on international opportunities. The marketing strategy of the stage-two company is extension; that is, products, advertising, promotion, pricing, and business practices developed for the home-country market are “extended” into markets around the world.

Almost every company begins its global development as a stage-two international company. Stage two is a natural progression. Given limited resources and experience, companies must focus on what they do best. When a company decides to go international, it makes sense at the beginning to extend as much of the business and marketing mix (product, price, promotion, and place or channels of distribution) as possible so that learning can focus on how to do business in foreign countries.

A fundamental strategic maxim is that it is a mistake to attempt to simultaneously diversify into new customer and new-product/technology markets.

The international strategist observes this maxim by holding the marketing mix constant while adding new geographic or country markets. The focus of the international company is on extending the home-country marketing mix and business model.

Stage Three—Multinational

In time, the stage-two company discovers that differences in markets around the world demand an adaptation of its marketing mix in order to succeed. Toyota, for example, discovered the former when it entered the U.S. market in 1957 with its Toyopet. The Toyopet was not a big hit: Critics said they were “overpriced, underpowered, and built like tanks.” The car was so unsuited for the U.S. market that unsold models were shipped back to Japan. The market rejection of the Toyopet was chalked up by Toyota as a learning experience and a source of invaluable intelligence about market preferences. Note that Toyota did not define the experience as a failure. There is, for the emerging global company, no such thing as failure: only learning experiences and successes in the constantly evolving strategy and experience of the company.

When a company decides to respond to market differences, it evolves into a stage-three multinational that pursues a multi-domestic strategy. The focus of the stage-three company is multinational or in strategic terms, multi- domestic. (That is, this company formulates a unique strategy for each country in which it conducts business.) The orientation of this company shifts from ethnocentric to polycentric.

A polycentric orientation is the assumption that markets and ways of doing business around the world are so unique that the only way to succeed internationally is to adapt to the different aspects of each national market. Like the stage-two international, the stage-three multinational, polycentric company is also predictable. In stage-three companies, each foreign subsidiary is managed as if it were an independent city-state. The subsidiaries are part of an area structure in which each country is part of a regional organization that reports to world headquarters. The stage-three marketing strategy is an adaptation of the domestic marketing mix to meet foreign preferences and practices.

Philips and its Japanese competition was dramatic. Matsushita, for example, adopted a global strategy that focused its resources on serving a world market for home entertainment products.

Stage Four—Global

The stage-four company makes a major strategic departure from the stage-three multinational. The global company will have either a global marketing strategy or a global sourcing strategy, but not both. It will either focus on global markets and source from the home or a single country to supply these markets, or it will focus on the domestic market and source from the world to supply its domestic channels. Examples of the stage-four global company are Harley Davidson and the Gap. Harley is an example of a global marketing company. Harley designs and manufactures super heavyweight motorcycles in the United States and targets world markets. The key engineering and manufacturing assets are all located in the home country (the United States). The only Harley investment outside the home country is in marketing. The Gap is an example of a global sourcing company. The Gap sources worldwide for product to supply its U.S. retail organization. Each of these companies is operating globally, but neither of them is seeking to globalize all of the key organization functions.

The stage-four global company strategy is a winning strategy if a company can create competitive advantage by limiting its globalization of the value chain. Harley Davidson gains competitive advantage because it is American designed and made, just as BMW and Mercedes have traded on their German design and manufacture. The Gap understands the U.S. consumer and is creating competitive advantage by focusing on market expansion in the United States while at the same time taking advantage of its ability to source globally for product suppliers.

Stage Five—Transnational

The stage-five company is geocentric in its orientation: It recognizes similarities and differences and adopts a worldview. This is the company that thinks globally and acts locally. It adopts a global strategy allowing it to minimize adaptation in countries to that which will actually add value to the country customer. This company does not adapt for the sake of adaptation. It only adapts to add value to its offer. It should be noted strengthening the transnational nature of the consolidation, accompanied by the growth of global multinationals.

The key assets of the transnational are dispersed, interdependent, and specialized. Take R&D, for example. R&D in the transnational is dispersed to more than one country. The R&D activities in each country are specialized and integrated in a global R&D plan. The same is true of manufacturing. Key assets are dispersed, interdependent, and specialized. Caterpillar is a good example. Cat manufactures in many countries and assembles in many countries. Components from specialized production facilities in different countries are shipped to assembly locations for assembly and then shipped to customers in world markets.

Shortly, the concept of TNC has gradually moved from international mentality to a multinational, then to the global and finally transnational mentality.

1.3 Classification of TNCs

A variety of TNCs which operate in the world can be classified into a number of signs. The cores from them: the country of origin, industry focus, size, the level of transnationalization.

The practical significance of the classification of TNCs is that it allows for more objectively estimating the advantages and disadvantages of placing specific corporations in a host country.

Country of Origin Country of origin is determined by the nationality of TNCs in the capital of its controlling stake assets. Usually, it coincides with the nationality of the country-based head company of the corporation. In the developed countries TNCs are considered as a private capital. However in the developing countries, the capital structure of some (sometimes large) part of TNCs may belong to the state. This is due to the fact that they were created on the basis of the nationalized foreign-owned or state-owned enterprises. Their goal was not into the economies of other countries, but their main purpose was to lift national economy.

Commodity Focus The global product is one approach to TNC organization. This is assigned worldwide responsibility for specific products or product groups in order to separate operating divisions within a firm. It means, what to produce for transnational corporations is really crucial. Commodity Focus TNC is defined by the basic sphere of its activity. On this basis, it is distinguished with TNCs which are adapted for raw materials, the corporations which are engaged in basic and secondary manufacturing industries and industrial conglomerates. Currently, multinational corporations maintain their position in the basic branches of mining and manufacturing industries. These are the areas of activity that require substantial investment. In the last years, more than 250 from the list of 500 largest transnational corporations in the world are operating in such areas as electronics, computers, communications equipment, food, beverages and tobacco, pharmaceutical and cosmetic products, as well as in the service of commercial services, including on the Internet.

Transnational corporations carry out various kinds of overseas research and development work: adaptive, ranging from basic support processes and ending with the modification and improvement of imported technologies, innovation associated with the development of new products or processes for local, regional and global markets and others.

The choice of the type of R & D (Research and Development) and industry specialization depend on what region, on what level of development there is a host country. For example, in Southeast Asia is dominated with innovative R & D associated with computers and electronics, in India - with the sector of services (especially software), in Brazil and Mexico - with the production of chemicals and transport equipment.

For transnational corporations, conglomeratic type with a view of definition of their specialization is called branch A, which the UN describes as having a considerable amount of foreign assets, the greatest quantity of foreign sales and the largest number of workers abroad. The largest part of corporation’s investment goes to this branch, and proportionally, it gives the greatest profit for corporation.

The size of transnational corporations

Symptom classification, which is usually determined by the method of UNCTAD, is defined by the size of their foreign assets. This parameter is especially used for the diversification of the largest TNCs, large, medium and small. In order to get the name large one, assets of transnational corporation should exceed 10 billion dollars.

The vast majority of the total number of TNCs (90%) belongs to medium and small corporations. According to the UN classification these include companies with fewer than 500 employees in the country of residence. In practice there are multinational corporations with total of employees less than 50 persons. The advantage of small TNCs is their ability which adapts more quickly to changing market conditions.

2 . THE ROLE OF TRANSNATIONAL CORPORATIONS IN MODERN ECONOMIC RELATIONS

2.1 TNC participation in international production

The economic and financial crisis has significantly affected TNCs’ operations abroad. Foreign affiliate’ sales and value-added declined by 4-6 percent in 2008 and 2009. Since this contraction was slower than the decline of world economic activity, however, the share of foreign affiliates’ value-added (gross product) reached a new historic high of 11 percent of world domestic product (GDP). Besides Greenfield investments, any expansion of the foreign operations of TNCs in 2009 can largely be attributed to the organic growth of existing foreign affiliates.

The world market is becoming more and more integrated. Within last ten years world trade developed much faster than world production grew. Foreign employment remained practically unchanged in 2009 (+1.1 percent). This relative resilience might be explained by the fact that foreign sales started to pick up again in the latter half of 2009. In addition, many TNCs are thought to have slowed their downsizing programmes as economic activity rebounded – especially in developing Asia. In spite of the setback in 2008 and 2009, an estimated 80 million workers were employed in TNCs’ foreign affiliates in 2009, accounting for about 4 percent of the global workforce.

Dynamics vary across countries and sectors, but employment in foreign affiliates has been shifting from developed to developing countries over the past few years; the majority of foreign affiliates’ employment is now located in developing economies. The largest number of foreign-affiliate employees is now in China (with 16 million workers in 2008, accounting for some 20 percent of the world’s total employees in foreign affiliates). Employment in foreign affiliates in the United States, on the other hand, shrank by half a million between 2001 and 2008.

In addition, the share of foreign affiliates’ employment in manufacturing has declined in favor of services. In developed countries, employment in foreign affiliates in the manufacturing sector dropped sharply between 1999 and 2007, while in services it gained importance as a result of structural changes in the economies.

Foreign affiliates’ assets grew at a rate of 7,5 percent in 2009. The increase is largely attributable to the 15 percent rise in inward FDI stock due to a significant rebound on the global stock markets.

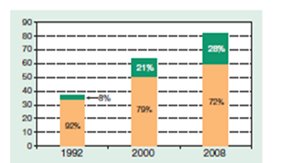

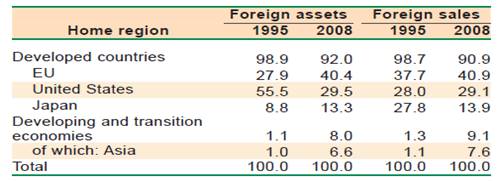

The regional shift in international production is also reflected in the TNC landscape. Although the composition of the world’s top 100 TNCs confirms that share has been slowly decreasing over the years. Developing and transition-economy TNCs now occupy seven positions among the top 100. And while more than 90 percent of all TNCs were headquartered in developed countries in the early 1990s, parent TNCs from developing transition economies accounted for more than a quarter of the 82,000 TNCs (28 percent) worldwide in 2008(2.1- table), a share that was still two percentage points higher than that in 2006, the year before the crisis. As a result, TNCs headquartered in developing and transition economies now account for nearly one tenth of the foreign sales and foreign assets of the top 5,000 TNCs in the world, compared to only 1-2 percent in 1995(2.1-picture).

Picture 2.1 -Number of TNCs from developed countries and from developing and transition economies, 1992, 2000 and 2008

Other sources point to an even larger presence of firms from developing and transition economies among the top global TNCs. The Financial Times , for instance, includes 124 companies from developing and transition economies in the top 500 largest firms in the world, and 18 in the top 100. Fortune ranks 85 companies from developing and transition economies in the top 500 largest global corporations, and 15 in the top 100.

Table 2.1 - Foreign activities of the top 5,000 TNCs, by home region/country, 1995 and 2008

Over the past 20 years, TNCs from both developed and developing countries have expanded their activities abroad at a faster than at home. This has been sustained by new countries and industries opening up to FDI, greater economic cooperation, privatizations, improvements in transport and telecommunications infrastructure, and the growing availability of financial resources for FDI, especially for cross-border M&As.

The internationalization of the largest TNCs worldwide, as measured by the transnationality index, actually grew during the crisis, rising by 1.0 percentage points to 63, as compared to 2007. The transnationality index of the top 100 non-financial TNCs

9-09-2015, 02:03